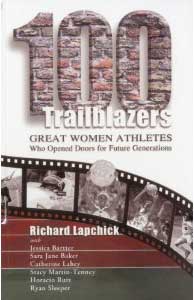

Mae Faggs Starr: Track & Field

American Star of the Women’s International Sports Hall of Fame

Photo: baysidehistorical.org

In an era of track and field superstars like Wilma Rudolph, it was easy to overlook Mae Faggs Starr. However, many people do not realize that a lot of Wilma Rudolph’s success can be attributed to Faggs Starr. The “Mother of the Tigerbelles,” as Faggs Starr was lovingly called, was a mentor to Rudolph and was responsible for the influx of talent that followed her at Tennessee State University. Besides being a trailblazer and pioneer for track and field, she remains one of most decorated sprinters in track and field history.

Perhaps Faggs Starr was willing to help others because she had been given a big break when she was younger. “When I was in elementary school a policeman came to school, and he was looking for some boys to run in a track meet for the Police Athletic League (PAL),” Faggs Starr recalls.1 A true tomboy, she ignored the boysonly invitation and joined them in the yard after school. Despite the policeman’s skepticism, he humored this small, young girl and lined Faggs Starr up to race against the boys. She easily beat the field. Although this impressed the policeman, he did not need a girl runner, but Faggs Starr did not care. She immediately began running with the PAL, and it was not long after that she caught the attention of an Irish sergeant named John Brennan.

Sergeant Brennan took Faggs Starr under his wing and began developing her talent and she quickly became the pride of the PAL and Brennan’s “ace in the hole.” His role in Faggs Starr’s life soon began to take shape, as it extended from simply serving as a coach to assuming the roles of being a father figure, mentor, and friend. Despite all the obstacles for an African-American woman during this period, Sergeant Brennan believed in Faggs Starr. In fact, during the summer of 1947, Faggs Starr recalls Brennan telling her, “Next summer they are going to have the Olympics and you’re going to make the Olympic team.”2

Sure enough, Brennan’s prediction was right. The next year Faggs Starr boarded the SS America to the XIV Olympiad in London as the youngest U.S. team member. The 16-year-old left behind her family and the person who had always been by her side, Coach Brennan, but even without that stability, she was unaffected. Even when she was placed in the same heat as the reigning gold medalist, she was unfazed, handling the pressure like a seasoned veteran. Despite placing third in her heat and failing to make the finals, Faggs Starr was not the least bit disappointed. She knew this would not be her last Olympic Games.

After seeing the intense international competition, Faggs Starr and Sergeant Brennan trained harder than ever. She competed in countless races to prepare for the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki, Finland. Before long, the 5-foot-2-inch, 100-pound Faggs Starr was competing against girls twice her size and twice her age. In one race, Brennan put her up against the current world record holder and reigning bronze medalist. He was not surprised when she defeated them both, but Faggs Starr exceeded his expectations by setting a new American record.

Faggs Starr again qualified for the Olympics, but the United States had very low expectations for the U.S. women’s track team competing in Helsinki. Many of the stars from the 1948 Olympics withdrew from competition, leaving a deflated team with low spirits and motivation. Faggs Starr, however, refused to give in to this negative outlook; instead, she used this determination as a motivational catalyst. After she placed sixth in the 100-meter, Faggs Starr’s last hope for a medal rested with her relay team. Realizing that winners and losers are only separated by mere seconds, Faggs Starr encouraged— and sometimes threatened—her team to practice handoffs. “Mae used coercion with her teammate Barbara [Jones]; she would refuse to do Barbara’s hair if the she would not come out for practice.”3 The practice helped seal the American team victory as Faggs Starr and her teammates Jones, Janet Moreau, and Catherine Hardy went on to win the gold medal in the 4 x 100-meter relay.

Fresh off of her Olympic success, Faggs Starr caught the attention of Coach Ed Temple at Tennessee State University. After being one of Coach Temple’s first recruits, she once again left her family and coach in Bayside, New York, and began a new chapter in her life. Once she arrived at Tennessee State, she quickly realized the track program was in dire condition. Not only was Faggs Starr one of two girls on the team, but the school did not have any money for travel and there were limited funds to cover expenses. To make matters worse, Faggs Starr was exposed to the segregation of the Deep South for the first time in her life.

However, Faggs Starr approached these obstacles just as she had all the others—with motivation and perseverance. Eventually, the team expanded and Faggs Starr, an Olympian and national champion, was the target for her young teammates. “My teammates, all they cared about in practice was running past Mae Faggs Starr. You couldn’t let your guard down.” Despite this increased competition, Faggs Starr was the stability of the Tigerbelles, reaching out to the others offering coaching tips, and sharing her experience.

When Faggs Starr qualified for the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, she became the first woman to compete in three consecutive Olympic Games. Nevertheless, in keeping with her nurturing personality, Faggs Starr spent time with one of her fellow teammates, rising star Wilma Rudolph, who entered the 1956 trials full of nerves and jitters. It was Faggs Starr who was partly responsible for helping Rudolph qualify for the Olympic Games:

I remember Wilma was nervous because she was so young, so I told her to do everything I did. Wilma agreed. So you see me, this 5-foot-2-inch person standing there and you see her, this 6-foot-tall girl, doing everything I did. If I bent over to touch my shoes to limber up, she bent over and did the same thing. If I raised my arm, she raised her arm. It quickly took her mind off her nerves as she tried to watch everything I did. That was the whole idea and it worked!4

Together with Margaret Matthews and Isabelle Daniels, they earned a bronze medal in the 4 × 100-meter relay. Four years later, Wilma Rudolph would become the first woman to win three Olympic gold medals. Although Faggs Starr was often overshadowed by Rudolph, the selfless Faggs Starr was always happy to help her young teammate.

Soon after Melbourne, Faggs Starr retired from the sport of track and field, but she continued to serve as a mentor. She earned her teaching certificate and embarked on a career that would last over 40 years. In addition to teaching, she also served as an athletic director and track and field coach at Princeton High School in Cincinnati.

In 2000, Mae Faggs Starr lost her battle to breast cancer. Her decorated career and impact on the sport of track and field will not soon be forgotten. She was inducted into the National Track and Field Hall of Fame and she is the holder of more than 150 medals, trophies, and ribbons. Mae Faggs Starr’s greatest contribution to the sport, however, is the impact she had on Tennessee State University. Although Mae Faggs Starr is often overlooked due to former teammates like Wilma Rudolph, it was Mae Faggs Starr who set the groundwork for these future stars.

Notes

1. Michael D. Davis, Black American Women in Olympic Track and Field (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1992), 50.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid., 55.

4. Lynn Sears, Suite101com, “Mae Faggs Starr,” http://www.suite101.com/article.cfm/running/5214 (accessed May 30, 2008).

This excerpt was written by Sara Jane Baker.

IN SEASON:

Tue, Oct 1 at 12:03pm

Fri, Sep 6 at 9:32am

Fri, Nov 8 at 9:29pm

Fri, Nov 1 at 4:39pm

Today at 9:09am

Today at 9:04am

Sun, Nov 10 at 6:59pm

Thu, Nov 7 at 9:08pm

LATEST ARTICLES & POSTS

posted by Swish Appeal

Mon at 9:13am

posted by Swish Appeal

Mon at 9:11am

posted by All White Kit

Sun at 6:42pm