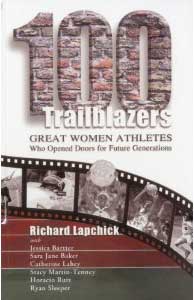

Merrily Dean Baker:

Trailblazer of the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW)

Photo: msuspartans.com

Merrily Dean Baker tells aspiring students and sport professionals to take three pills at the start of every day: one for courage, a second for commitment, and a third for compassion. It was, she says, these three characteristics that carried her through a career in athletics that saw her build athletic programs from scratch and blaze a trail for women by going where many had never been before. It would take a lot of courage, commitment, and compassion for Baker to work beneath a constant microscope. The challenges of running athletic departments were very real, but for Baker, sometimes the challenges went beyond the job description.

“Virtually every job I had I was the first woman there or starting a new program,” she said. “I had to assure people that it was okay that I was there and that I was able to do it. Everywhere I went people were not used to having a woman as a boss.”1

Initially drawn to a career in teaching and coaching, Baker received her undergraduate degree in physical education from East Stroudsburg University, where she was a six-sport athlete. From an early age, Baker was involved in athletics, as her father taught her how to swim when she was three years old and she started competitive field hockey by the fifth grade. She would continue a coaching career in gymnastics and field hockey through the university and high school ranks before finishing her master’s degree in fine arts and dance in 1968 from Temple University. Baker took her first administrative position in 1969 at Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, as the university’s first director of the women’s athletic department. In 1970, Princeton University asked her to be a consultant for its new women’s athletic department. After three days of consulting at Princeton, the university offered her their position as the women’s director of athletics.

“I felt like that was raising another child,” said Baker of Princeton. “I started the Princeton athletic department from scratch. We started with nothing; they handed me a five-year plan that was a slow progression.” Initially, Princeton had intended for Baker to plan and implement a women’s athletic department in five years, but after consulting with the women on campus, the five-year plan was scrapped in three weeks. Women wanted to participate in sports a lot sooner and Baker eagerly undertook the challenge of building an athletic department for them. She implemented some of the first sports women would play at Princeton, including basketball, field hockey, tennis, swimming, and lacrosse. “Princeton women’s athletics did extremely well,” Baker said. “Everybody loves winners and the Princeton teams, from day one, won championships. It set the tone for acceptance of women in a very major way.” The 1970s was a decade of great professional and personal growth for Baker. She would spend 12 years at Princeton as the women’s athletic director, and she would also marry and become a mother. Baker also became a leading proponent for women’s athletics on the national level by working with the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW). Under the AIAW, Baker played a crucial role in lobbying for Title IX legislation, which would give women in universities more opportunities to play sports at the collegiate level. But with the passing of Title IX came the dissolution of the AIAW. What was then strictly a male-only National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) absorbed the AIAW with its far more expansive financial resources to fund women’s athletics.

Baker was the last president of the AIAW, where she was tasked with holding together an organization that would soon disappear. Baker and her colleagues made one more attempt to preserve the organization with a lawsuit against the NCAA, but they lost.

“Donna Lopiano and I spent hours and hours in D.C. getting ready to file that suit,” Baker said. “We all had to testify in federal district court. They found the NCAA not in violation of antitrust laws. We could not compete with their financial resources. I was talking to women who were professional friends for years. It was a very difficult time emotionally and all I could do was traverse the country and calm people down. All of us grew up in the AIAW. Before the AIAWI knew nothing about politics. I was thrust into leadership positions with people telling me I was their mentor before I had found a mentor for myself. We were thrust into positions where somebody had to do something and so you did what had to be done.

We all experienced tremendous personal and professional growth. I certainly didn’t expect that my presidential experience would be to shut out the lights and close the door. But it was a decade-long experience that gave birth to women’s intercollegiate athletics today. Women’s sports survived and it got better. The AIAWwasn’t a failure. The AIAWwas a huge success. It set the stage for what is happening today. Do not ever look at the AIAWas a failed experiment— it was a very successful experiment. So successful that someone took it over. I feel privileged to have been part of the leadership. I will be forever grateful to that opportunity and to the people that made it happen. It has shaped all of us.”

In 1982, Baker was wooed to the University of Minnesota as the athletic director of the women’s athletic department. Under her leadership the department took women’s athletics to a higher level, increasing the amount of scholarship money available to its athletes and also getting the State of Minnesota to finance the operations of the women’s athletic departments due to her lobbying efforts. Baker was also able to secure a television contract for the women’s athletic department. In 1988, her final year at Minnesota, she was named one of the “100 Most Powerful Women” in the United States by the Ladies’Home Journal. She also coauthored an $85 million athletics facilities plan that was part of the university’s effort to build an Aquatics Center that opened in 1990. For all her efforts in her tenure at Minnesota, she was inducted into the M Club Hall of Fame in 2005.

Baker can laugh with colleague Christine Grant about their first Big Ten athletic director meeting. At the time, Baker and Grant were both directors of the only separate women’s athletic departments in the Big Ten, and they were the only women at the meeting. Baker and Grant were asked by another athletic director if they would mind stepping out of a picture at the resort where the meetings were being held. They did not step out of the picture. But they would later find out that there was another picture taken in the back of the resort of all the athletic directors—excluding them.

“They were products of their upbringing but it didn’t make it any more palpable to deal with,” Baker said. “Every single man was fine with us one on one, but in a group it was different. The worst of them I could have dinner with or have a drink with and we would be fine. But then they would get with their buddies and their attitude would be completely different. I tried to change it instead of being angry about it.”

After serving in the Big Ten with Minnesota, Baker calls her career between 1988 and 1992 at the NCAA her corporate piece because it was the only time she was not working on a college campus. Baker was convinced by then–executive director of the NCAA Richard Schultz to serve as the assistant executive director of the NCAA. Schultz convinced Baker to join the NCAA by telling her that what she could do for 100 schools she was doing for one. It took Baker nine months to make a decision, but she ultimately accepted. She became the first woman appointed to the NCAA Executive Committee. Some of her colleagues could not understand why Baker would work for the NCAA after it absorbed the AIAW, but she saw the NCAA as a continuation of her and her colleagues’ hard work in the 1970s. “I suddenly was now on the Executive Committee of the enemy,” she said. “We spent 10 years building something that we really believe in and this is the organization that is going to continue this and I want to make sure it’s done right.”

At the NCAA, Baker created scholarship and internship opportunities for women and ethnic minorities. She wanted to create more professional opportunities and to enhance their education. She administered two national youth programs that served more than 67,000 youth each year through sport and education enrichment programs. She also initiated the NCAA Student-Athlete Advisory Committee (SAAC), which gave student-athletes a voice in matters concerning them.

In 1992, Michigan State University (MSU) called and Baker headed back to the Big Ten as the first woman to be named athletic director at the conference and only the second at a Division I football- playing institution. Only four years after returning to the Big Ten, Baker could sense a different level of respect from her peers, because, as she puts it, a new generation of administrators had taken up the athletic director posts and “a lot of the old-timers had retired by then.” Baker’s arrival at Michigan State was not without its share of turmoil. On her first day on the job, the president that hired her called Baker at her office. Thinking she was receiving a phone call wishing her good luck on her first day, she soon realized that the president had instead called to inform her that he was resigning. Baker would serve under three presidents her first two years at Michigan State. During her time at Michigan State, she was able to fundraise at higher levels than her predecessors while increasing student-athlete graduation rates and concentrating on enrichment programs for student-athletes, including community outreach and mentor programs. But she was also stifled by what she says was the most political institution she had ever been involved with. At one point she had a trustee of the university telling her to cheat.

“It was a cauldron of controversy at Michigan State,” Baker said. “I never shied away from challenges before so I said let’s get on it. I met wonderful people. It’s a wonderful institution, it just happened at a time when they subjugated their values for politics. There are parts of me that had the energy to stay longer and accomplish some things. To me, MSU was an institution that lost its moral compass. I had to look in the mirror and I said I can’t do it. It was probably the most challenging of all the experiences I had. I feel very good about the things we accomplished and the things we got done.”

Baker resigned from Michigan State in 1995, but even amid detractors who said she could not deal with managing football, men’s basketball, and men’s hockey, one of her greatest legacies was hiring basketball coach Tom Izzo. At the time of his hiring, Baker was criticized for elevating Izzo from the assistant coach position to the head coach position in 1995. “I felt Tom was the hire to make,” she said. “A lot of the old boys gave me a lot of grief that he’s too young, he’s too that.”

But in 1999, when the Michigan State basketball team made the Final Four for the first time in Izzo’s tenure, he called Baker to tell her that he never forgot who hired him and that she was welcome to as many tickets to the Final Four as she wanted. She accepted the invitation. The next season, she again accepted Izzo’s invitation to the Final Four when the Spartans won their second basketball national championship in school history. Baker partied along with all the other people that had criticized her years before for hiring Izzo.

In 1998, she was asked to be a part-time consultant for Florida Gulf Coast University, which was starting an athletic department from the ground up. What was supposed to be a six-month job to write a 10-year strategic plan and to help fundraise, turned into two and a half years during which she was appointed as the interim athletic director. She hired the first four coaches at the university for the men’s and women’s and golf and tennis teams. “It was another start from scratch,” Baker said. “It was an incredible experience. Someone handed me a blank slate and they said to me, ‘Fill it.’”

Looking back on her career, Baker says one of the most difficult parts was balancing her work with her family life, but she found ways to make it work. She also encouraged her coaches to bring their kids to sporting events, and she let them know it was okay to incorporate their family into their careers. It wasn’t accepted by all people, but Baker knew her responsibilities lay in being both a mother and a professional. At Michigan State, Baker made it a point to leave every Thursday at 4:00 p.m., with no exceptions, because her daughter needed to be at her Girl Scout troop meeting. “I did it with three children in tow,” Baker said. “I did it when it wasn’t supposed to be done. I really didn’t have any role models or mentors that fit what my life was like. I wanted other women to know they could have this career and still have a family. You have to find ways to make it work, but you can make it work without question.”

Baker said someone once told her it takes three generations to have changes truly take place. Two generations have passed since she became a leading voice for the passage of Title IX through the AIAW, so she thinks it should be soon when she will see the fruition of her labors and women will be on a level playing field.

“I was so blessed to have all these opportunities and experiences,” Baker said. “It was not all a bed of roses. But rewarding? Absolutely. We all met people who helped us along the unknown path. A lot of trial and error, a lot of mistakes were made, but you have to be strongly committed to stand up for what’s right. The overall joy is it stretched over 38 years and I had a lot of opportunities to go where a lot of women did not have opportunities to go. I’d do it all again in a minute.”

Note

1. All of the quotes in this article are by Merrily Dean Baker, from an interview with the author on July 11, 2008.

This excerpt was written by Horacio Ruiz.

IN SEASON:

Tue, Oct 1 at 12:03pm

Fri, Sep 6 at 9:32am

Fri, Nov 8 at 9:29pm

Fri, Nov 1 at 4:39pm

Today at 9:09am

Today at 9:04am

Sun, Nov 10 at 6:59pm

Thu, Nov 7 at 9:08pm

LATEST ARTICLES & POSTS

posted by Swish Appeal

Mon at 9:13am

posted by Swish Appeal

Mon at 9:11am

posted by All White Kit

Sun at 6:42pm