Marcenia "Toni Stone" Lyle Alberga: Baseball

American Star of the Women’s International Sports Hall of Fame

Photo: blackamericaweb.com

Upon first glance, there was nothing unusual about the 1953 Negro League baseball game taking place in Omaha, Nebraska, that Easter Sunday afternoon. Legendary pitcher Satchel Paige was on the mound throwing a no-hitter for the St. Louis Browns. As another probable strikeout victim entered the batter’s box, Satchel, as he often did just to give the opposition a chance, asked where the batter wanted him to throw it. “You want it high? You want it low? You want it in the middle? Just say. How do you like it?” The batter responded, “It doesn’t matter.”1 The batter then proceeded to lace a single right over Satchel’s head into center field. Overjoyed by this rare occurrence, the batter barely made it to first base and fell while rounding the bag. The batter would later describe this as the happiest moment in her life. Not surprisingly, this was the only hit Satchel allowed that day. In fact, there was really only one surprise that day when it was revealed the batter was actually a woman.

Toni Stone, born Marcenia Lyle, became the first woman to play professional baseball when she broke the gender barrier in 1953.2 She learned to play the game on the playgrounds of St. Paul, Minnesota, where she was raised by her father, a barber, and her mother, a beautician. “They would have stopped me if they could,” Stone recalls, “but there was nothing they could do about it.”3 Unlike most women, she did not get her start in softball. She played pickup games of baseball with the boys in her neighborhood, and later in the Catholic Midget League. As a child, determined to participate in the sport she loved, she collected Wheaties cereal box tops to exchange for a chance to be in a baseball club the cereal was sponsoring. She realized from an early age that she was different from the other girls and described herself as an “outcast” because she was not interested in adopting traditional roles reserved for women.4 Gabby Street, the big league catcher and later manager of the world champion St. Louis Cardinals, was a huge influence on Stone in her early playing days. After he was demoted to managing the minor league team, the St. Paul Saints, he established a baseball school near Stone. After she pestered him enough to play, she was finally given a chance to participate. When Gabby saw of what Stone was capable, he sponsored her by buying her a pair of cleats and admitting her into his school.

When Stone was 15 years old, she moved to San Francisco with less than a dollar in her pocket to find an ailing sister. This move would prove propitious for Stone’s career in professional baseball. After bouncing between jobs, doing everything from making salads in a cafeteria to operating forklifts in the shipyards, she discovered Jack’s Tavern, a popular social-gathering place for African-Americans. There she met tavern-owner, Al Love, who helped her get a spot on an American Legion team.5 From there she earned a roster spot on a semiprofessional team called the San Francisco Sea Lions. However, she soon began to feel like the owner was not paying her what he had promised. As she became accustomed to a career in a male-dominated society, Stone learned to stand up for herself.

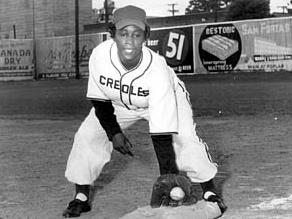

Upon receiving a better offer from another team while on a road trip through New Orleans, she decided to stay and play for the New Orleans Black Pelicans, a Negro League farm team. She would eventually move to the New Orleans Creoles, another farm team for the Negro League, where she made up to $300 a month.6

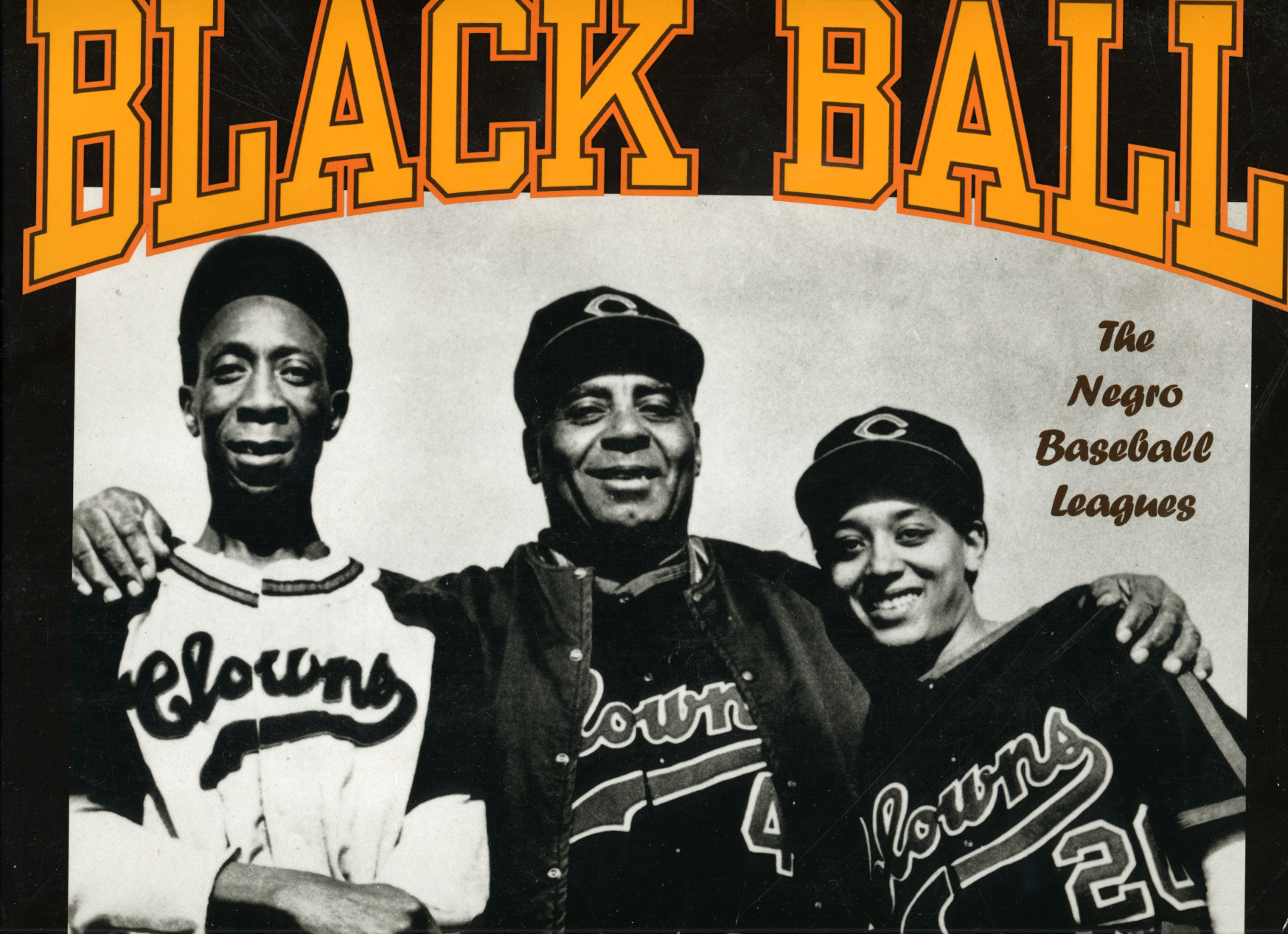

Stone’s big break in baseball would come in 1953, when Syd Pollack, owner of the Indianapolis Clowns, signed her to her first major league contract. The Clowns, a major Negro League team, were often referred to as the Harlem Globetrotters of baseball. They earned this reputation because of their frequent publicity stunts, but the Clowns’ owner insisted that hiring Stone was a legitimate baseball move. In his defense, the Clowns had toned down their antics, and were actually one of the top-rated teams when she was signed, having won the league championship in 1950. Also, the team really did need to fill a void at second base. After all, their previous second baseman’s contract had just been sold to the Boston Braves for $10,000 after he batted .380 for the Clowns.7 The player Stone replaced was Henry “Hank” Aaron.

It is interesting to note that Stone might not have had the opportunity to break the gender barrier in baseball if Jackie Robinson had not broke the color barrier in baseball just six years earlier in 1947. As a result, many of the best African-American players defected to Major League Baseball, and therefore, the Negro League owners had to look toward new avenues to compete on the field and at the gate. The irony is, Stone originally sought out to break the color barrier in women’s baseball in the All-American Girls Baseball League, but upon being turned away because of the color of her skin, she went back to what she was accustomed to, playing on teams with all men and defied history. She really had no interest in being the first woman to play in men’s baseball, only that she had an opportunity to play at all. “I come to play ball,” she declared after signing with the Clowns. “Women have got just as much right to play baseball as men.”8

While some players and fans were receptive to this pioneer, she also gracefully endured a great deal of sexist treatment. One of the first things requested of her upon her move to the major leagues was that she wear a skirt while playing to add sex appeal to the games for male spectators. Again, being the strong woman that she was, she refused to do so saying, she would quit before accommodating that particular idea. Stone was also frequently the victim of “spikes-up” slides at second base from male players who resented having to share the field with a woman. Sliding with the spikes on the bottom of the cleats “up,” or toward the fielder, is an unsportsmanlike action with the intention of physically harming the opposition. Once, one of her own teammates even lobbed the ball to her for a play at second base in order for the play to take longer to develop, increasing the probability of a collision. Stone prided herself on standing in to take the unwarranted punishment and still make the plays, even bragging about the scars on her legs from her playing days.

Beyond the unequal treatment from her co-workers was the routine emotional abuse from the fans. “They’d tell me to go home and fix my husband some biscuits, or any damn thing. Just get the hell away from here,”9 remembers Stone. The press was also often unkind. Doc Young of the Chicago Defender once wrote, “Girls should be run out of men’s baseball on a softly padded rail for their own good. This could get to be a woman’s world with men just living in it.”10 Being the humble and forgiving woman that she was, she reacted by saying, “They didn’t mean any harm and in their way they liked me. Just that I wasn’t supposed to be there.”11 That last point is arguable, as Stone was touted as a solid infielder who frequently made unassisted double plays at second base and batted a respectable .243 in her 50 games with the Clowns before being traded to the Kansas City Monarchs.

Following an unpleasant year in Kansas City where she did not receive a lot of playing time, Stone retired after the 1954 season. She moved back to Oakland, California, with her husband, Aurelious Alberga, who was a pioneer in his own right, being credited as the first black officer in the U.S. Army.12 She worked as a nurse in Oakland for many years, but continued to play recreational baseball until the age of 60. Toni Stone passed away in 1996 of heart failure at the age of 75. She was honored before her death when St. Paul, Minnesota, declared March 6, 1990, as “Toni Stone Day.” She would later have an athletic field and a play named after her in St. Paul. The play, Tomboy Stone, paid homage to her chosen nickname, Toni, which she picked because it sounded like “Tomboy.” Tributes to Toni Stone can be found in the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, as well as in the Negro League Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri. Stone once told a teammate, “A woman has her dreams, too.”13 Being such a modest human being, grateful just to play baseball, I would have to doubt that even in her wildest dreams she could imagine her story being such a lasting inspiration to female athletes all over the world.

Notes

1. Gai Berlage, Women in Baseball (Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 1994), 128.

2. Barbara Gregorich, Women at Play: the Story of Women in Baseball (San Diego, Calif.: Harvest, 1993), 173.

3. Ibid., 169.

4. Judy Hasday, Extraordinary Women Athletes (Danbury, Conn.: Children’s Press, 2000), 46.

5. Martha Ackmann, “Baseball Was Her Game,” SFGate, March 12, 2006, http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/chronicle/archive/2006/03/12/ING4THKSUN1.DTL (accessed February 9, 2008).

6. Gregorich, Women at Play, 171.

7. Ibid., 173.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid., 174.

10. Ackmann, “Baseball Was Her Game.”

11. Gregorich, Women at Play, 174.

12. Ibid., 175.

13. Hasday, Extraordinary Women Athletes, 45.

IN SEASON:

Tue, Oct 1 at 12:03pm

Fri, Sep 6 at 9:32am

Fri, Nov 8 at 9:29pm

Fri, Nov 1 at 4:39pm

Today at 9:09am

Today at 9:04am

Sun, Nov 10 at 6:59pm

Thu, Nov 7 at 9:08pm

LATEST ARTICLES & POSTS

posted by Swish Appeal

Mon at 9:13am

posted by Swish Appeal

Mon at 9:11am

posted by All White Kit

Sun at 6:42pm