Dr. Tenley E. Albright: Skating

American Star of the Women’s International Sports Hall of Fame

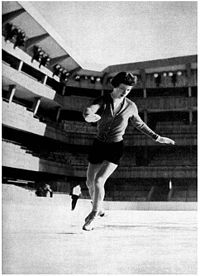

Supremely graceful and breathtakingly beautiful, Tenley Albright was the toast of the American figure skating scene in the 1950s. Watching Albright joyfully dance across the ice was like watching an artist turn a blank canvas into a masterpiece. Known for her innovative jumps and spins, Albright was also a master of the compulsory components of her routines. She approached her craft with both style and precision.

Albright excelled at competitive figure skating at a time when the sport was prized for its delicacy, grace, and feminine beauty. Though Albright appeared to fit the traditional image of the privileged, ultra-feminine figure skating icon, this public façade masked a complex array of talents, interests, and conquered challenges. The daughter of a prominent Massachusetts surgeon, Albright was diagnosed with polio at age 11, in an era when little was known about the disease’s process, treatment, or cure. The Albright family was warned that young Tenley might never walk again, much less pursue her interest in figure skating. During her treatment, Albright endured several painful procedures and was restricted from moving her back, neck, and legs.1

Finally, after months of hospitalization, Albright’s doctors slowly challenged her to take a few steps at a time. She met each test with determination and her condition began to steadily improve. Upon her release from the hospital in 1946, her doctors recommended that she return to skating, as the familiar and fun activity might help her reacclimate to “normal” life.

Her first time back to the rink, Albright clung to the barriers—unsteady and unsure on the ice. Just as she had done in the hospital, Albright began to challenge her body to surpass its physical barriers. As an adult, Albright wondered if this recovery process may have sparked her lasting interest in figure skating. “When I found that my muscles could do some things, it made me appreciate them more. I’ve often wondered if maybe the reason [figure skating] appealed to me so much was that I had a chance to appreciate my muscles, knowing what it was like when I couldn’t use them.”2

Buoyed by the excitement of using her muscles freely, Albright won the Eastern Juvenile Skating Championships only four months after being released from the hospital. This win marked the beginning of a long string of successes in Albright’s figure skating career. At the age of 16, Albright stepped into the international spotlight by winning a silver medal at the 1952 Winter Olympic Games in Oslo, Norway. Back at home that same year she continued her winning ways, earning the first of five consecutive national titles.

In 1953, Albright reached a number of milestones. Athletically, she became the first American woman to win a world figure skating championship. To this achievement, she added the titles of North American and U.S. Champion, making her the first winner of figure skating’s elusive “triple crown.” Personally, Albright enrolled in Radcliffe College, declaring a pre-med major. While other students enjoyed a leisurely collegiate experience, Albright practiced skating from 4:00 a.m. to 6:00 a.m. before tackling her daily studies.

This dedication to her craft paid off as she won the 1955 World Championships and qualified to skate in the 1956 Winter Olympics in Cortina, Italy. An accomplished student, Albright left Radcliffe to focus on her Olympic performance. Two weeks before the competition, Albright fell while practicing and sustained a serious cut to her right ankle. Immediately, her father flew to Italy in order to repair the damage to both vein and bone. Just as she had done while recovering from polio, Albright persevered through the pain. Her brilliant Olympic performance earned her the gold medal, making her the first American woman to achieve such a feat in figure skating.3

Upon her return to the United States, Albright shifted her focus back to the world of academia. Though she had not officially graduated from Radcliffe, she applied to Harvard Medical School. After seven interviews, she became one of only five women accepted to a class of 135 total students. Again, she persisted against the odds, eventually becoming a successful surgeon and a leader in blood plasma research. She also maintained her ties to skating by becoming the first woman to serve as an officer on the U.S. Olympic Committee and as an inductee into the World Figure Skating and Olympic Halls of Fame.

Highly successful as both a figure skater and a doctor, Albright lives her life according to some advice she received from her grandmother while still in high school. A teacher questioned Albright about why she continued to do something “as frivolous as” figure skating when she had aspirations of undertaking the very difficult and serious task of becoming a surgeon. Albright realized that she didn’t have an answer. She mentioned the conversation to her grandmother, who gave her some advice she would never forget “You have an obligation to do the best you can with whatever you’ve got. And if you like to do a sport, and you can do it well, that’s a way of expressing what God gave you.”4 Her grandmother would be proud of Albright’s adherence to these principles. Dr. Tenley Albright, a figure skating champion, prominent surgeon, and groundbreaking medical researcher, has certainly done the best with what she has been given.

Notes

1 “Dr. Tenley E. Albright,” Biography, Changing the Face of Medicine, http://www.nlm.nih.gov/changingthefaceofmedicine/physicians/biography_3.html.

2 Tenley Albright, interview, Academy of Achievement, June 21, 1991.

3 “Albright, Tenley,” Figure Skating Legends, United States Olympic Committee, http://www.usoc.org/26_13369.htm.

4 Tenley Albright, interview, Academy of Achievement, June 21, 1991.

This excerpt was written by Catherine Lahey.

IN SEASON:

Tue, Oct 1 at 12:03pm

Fri, Sep 6 at 9:32am

Fri, Nov 8 at 9:29pm

Fri, Nov 1 at 4:39pm

Today at 9:09am

Today at 9:04am

Sun, Nov 10 at 6:59pm

Thu, Nov 7 at 9:08pm

LATEST ARTICLES & POSTS

posted by Swish Appeal

Mon at 9:13am

posted by Swish Appeal

Mon at 9:11am

posted by All White Kit

Sun at 6:42pm