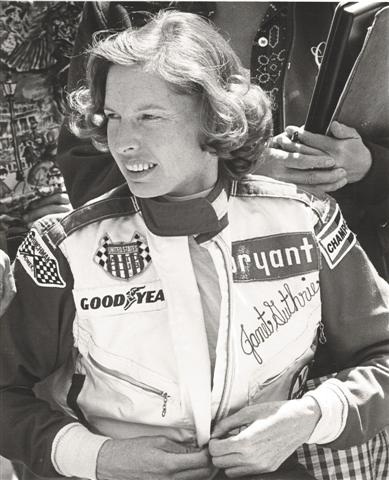

Janet Guthrie: Motorsports

American Star of the Women’s International Sports Hall of Fame

Website: http://www.janetguthrie.com/

There was no place to turn, no place to hide for Janet Guthrie, and pretend those people hadn’t said those things or behaved the way they did. Maybe it was a bit of a surprise, to have young males wishing she would crash or to be asked by the national media if she was a lesbian. Maybe it hurt when a fellow Indy driver said he could teach a hitchhiker to be a better driver than she could ever be or to have Richard Petty, the man they call “The King,” say she may be a woman, but she sure as heck is no lady.

On second thought, there was a place to hide—inside the racecars she loved to drive so much that would let her turn the wheel around the corners of the impossibly hallowed Indianapolis Speedway. But when she brought the car to a halt at Indy’s Gasoline Alley, took her helmet off, and got out of the cockpit, there came back the spotlight, showering her as much with rays of light as with the insults she would carry in her memories the rest of her life. But she didn’t want to hide, she just wanted to race, and maybe the things all those people said did hurt, but she could easily laugh it all off.

So when Guthrie, in 1976, attempted to qualify for the Indianapolis 500 and failed less because of her ability and more because of a car that just couldn’t compete, there’s no telling how many people gladly said to themselves or anyone willing to listen, “Told you so.” Did they know about her past? That she had been racing for 13 years, first with a Jaguar XK 120 and then with a 140 model while winning in the highly competitive Sport Car Club of America circuit, many times being the mechanic and sleeping in the back of cars to save money? By the time she decided to concentrate on racing full-time in 1972, she purchased a Toyota Celica and converted it into a racing vehicle, continuing her career as a racecar driver. In 1975, as a veteran racer and in the middle of a tough financial situation, she thought to herself, “One day you really must come to your senses and make some provision for your old age.”1 Then came her big break a year later, when car owner Rolla Vollstadt invited her to test-drive a car at the Indianapolis race track. Vollstadt wanted a woman racer, and after doing his research, it was Guthrie to whom he was always referred. Did they know?

Bruton Smith knew. Smith, a track promoter in Charlotte, watched the media circus following Guthrie at Indianapolis. He could see that by inviting her to his track in Charlotte for the World 600, she would become an instant draw. “I think it was jealousy. I was jealous of her being at Indianapolis,” Smith said. “I knew in my mind that she should be here. I never met her, but I knew of her ’[JB1] cause Janet had a lot of experience driving sports cars.”2

Guthrie had invested herself emotionally and physically to making the field at Indianapolis. She initially did not want to consider an alternative form of racing, but given the choice between watching at Indianapolis and taking a crack at stock car racing, the choice was simple. It seemed as if Guthrie would again repeat the car woes at Charlotte she had experienced at Indianapolis, but it was Junior Johnson, a racing legend as much for his victories as for being a key figure in the history of NASCAR, who took Guthrie under his wing. Johnson was one of the good ole boys and a former moonshiner who first ran fast cars to outrun the police who were chasing him for trafficking homemade whiskey across state lines. Guthrie could not get her car to run faster than 141 mph, so after Johnson and Hall of Fame driver Cale Yarborough tested the car and could not run it any faster themselves, both Johnson and Yarborough decided to give Guthrie their racing setup. “When a newcomer came into the sport, if he was in trouble, my team would help him out,” Johnson said. “She wasn’t no different. She was a race driver. She needed help. We helped her. We’d do it again.”3

She would qualify for the race in the row just behind Dale Earnhardt Sr. and Bill Elliott, and finished the race in 15th place. Guthrie was exhausted and suffering from carbon monoxide inhalation by the end, having become the first woman to compete in a NASCAR Winston Cup super speedway.

In 1977, she would be back at Indianapolis, becoming the first woman to race in the Indy 500. She set the fastest time of any driver in the opening day of qualifying, and also set the fastest qualifying time on the second weekend. Guthrie would finish 29th in her debut as the result of engine trouble, but would race twice more at the track. In 1978, she became the first woman owner/driver in Indy racing, responsible for hiring the crew, housing the crew, and purchasing car parts while handling the media and racing duties. She would go on to finish ninth, an Indy 500 career-best. In 1977, she would also become the first woman to race in the Daytona 500. Guthrie was in eighth place 10 laps from the finish at Daytona when engine problems again derailed her. She would still finish as the top rookie of the race while taking 12th place. At the Daytona 500 in 1980 she would turn in an 11th-place finish. Guthrie raced in 33 NASCAR races over four years, recording five top 10 finishes. She would also race in 11 Indy car races, her most successful race coming in the 1979 Milwaukee 200 when she finished fifth. Ironically, it would also be the last Indy race of her career. The money well had dried up. She could only find top sponsors for three years. She has no answer as to why, coming off a career-best finish, there suddenly was no money. “I wish I had been able to go on, but no money, no race,” Guthrie said. “That remains a problem for many women athletes. I was shocked and dismayed. You can compare my record in my 11 Indy-car races with the first 11 Indy-car races of any of the superstars, and I think you would find the comparison quite decent. I had a hard time reconciling myself to that. It was a sport I loved very much.”4

Maybe it hurt when people said those things and behaved the way they did, but it really hurt when she wanted to race so badly and couldn’t. From 1979 through 1983, she was regularly in New York City looking for corporate sponsors, but then “I realized that if I kept looking for sponsors I would jump out a window,”5 she says.

Guthrie retreated to her home in Aspen, Colorado, and channeled her frustration into what would become a 1,200-page manuscript detailing her racing experiences from the perspective as both a driver and as a woman in the driver’s seat. In 1980, she was in the first group of women ever inducted into the Women’s International Sports Hall of Fame. In 2006, she would be inducted into the International Motorsports Hall of Fame. In 2002, she made her way back to the Indianapolis 500, and for the first time ever, asked for an autograph from a 19-year-old woman named Sarah Fisher—the youngest and third woman ever to compete in the Indy 500. Fisher signed it, “To Janet, my idol.”

In 2005, she released a book, having edited her 1,200-page manifest into a 300-page autobiography entitled Janet Guthrie: A Life at Full Throttle. It was a work of labor 25 years in the making. Her hope was, and still is, to inspire women that follow her footsteps and to let the world know what it was like taking those footsteps. “Someday, a woman will win the Indianapolis 500; someday, a woman will win the Daytona 500,” Guthrie wrote in the final paragraph of her book. “I wish I could have been that driver. I hope some reader of this book will be.”

Guthrie still follows many of the women in the Indy racing circuit today, analyzing their performances when she gets the chance. For the 2008 Indianapolis 500, Guthrie will take part in a Saturday night fundraiser fashion show, joking that she needs to somehow find a way to lose 10 pounds. On Sunday, when the race is beginning, the woman who helped shape the history of the world’s most famous race will be on a plane returning home.

“I really don’t like watching it if I’m not racing. It’s because I didn’t,” Guthrie sighs, “quit willingly.”6

Notes

1 Janet Guthrie, interview with author, April 15, 2008.

2 Janet Guthrie Transcript. http://www.lowesmotorspeedway.com/news_photos/press_releases/507342.html, May 9, 2006.

3 Ibid.

4 Barbara Huebner, “Guthrie: Pioneer Who Was Driven—Her Perseverance Overcame Sexism,” The Boston Globe, October 20, 1999.

5 Janet Guthrie, interview with author, April 15, 2008.

6 Ibid.

This excerpt was written by Horacio Ruiz.

IN SEASON:

Tue, Oct 1 at 12:03pm

Fri, Sep 6 at 9:32am

Fri, Nov 8 at 9:29pm

Fri, Nov 1 at 4:39pm

Today at 9:09am

Today at 9:04am

Sun, Nov 10 at 6:59pm

Thu, Nov 7 at 9:08pm

LATEST ARTICLES & POSTS

posted by Swish Appeal

Mon at 9:13am

posted by Swish Appeal

Mon at 9:11am

posted by All White Kit

Sun at 6:42pm